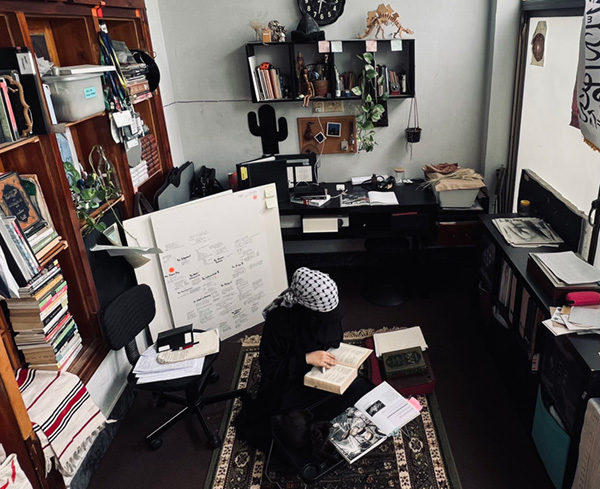

Sarah Khan

The 800-lettered piece, ‘د روح د اناټومې ته د سپوږمئ شاهدې’ (transliterated as ‘Da rooh da anatomy ta da spogmay shahidee’; translated as ‘An astral witness to the anatomy of a soul’) is the artist’s emotions surfaced as rhetorical sarcasm. Grounded in the futuristic facts learned from the religious scripts and written in Pashto—her mother tongue, already the fourth language spoken in space since 1988, will now make its mark on the Moon for the first time.

The literary work was first directed at herself; it wasn’t meant to lampoon the public but to create space for rethinking—to invite deep and powerful reflection. Artist by nature, but trained as a biologist, she switched from programming bacteria for sensing applications and delving into the prospects of lab-grown spacesuits which relied on engineered biomaterials, 3D-bioprinting and Cubesat technology. In her own way, she attempted to uncover cosmic secrets by initiating foundational research in her country—where meteoritic studies have

been overlooked, through investigations on lunar meteorites.

Embracing the challenge of addressing pivotal, long-established scientific puzzles and offering theoretical as well as experimental answers to questions such as, are we alone in the universe? What's the origin of life on Earth? She still often found herself frozen in silence (wrestling with the frustration of being only human) pondering religion-based scientific concepts that remained beyond her grasp. Ideas such as: everything illuminated like the sun and stars, is made from the light of God, or the notion of ‘eternity’, something we somehow know, yet can never fully experience in this life.

The question posed by the Moon Gallery Foundation finally gave her a chance to render the Moon’s thoughts, the continuously watching, yet non-participating celestial body. It opened the door to holistic questions, such as: why does the Moon exist in the first place? What is its presence pointing us toward? Is it a mirror of our consciousness, or a keeper of something older than memory? If everything illuminated comes from divine light, what then is the Moon reflecting back to us—only luminescence and calendar, or serious reminders, or the divinity itself?

Can the newly evolved Homo sapiens, late in their arrival to the story of the universe, grasp a truth older than time itself? Can observation, from the core of the scientific method, advancing as we are—building equations, maps and technologies—enough for species still figuring out its place in the universe(s)? Can imagination, the vast realm of artists, no matter how far-reaching, reach the fundamental nature of reality?

If we have established useful theories and shared stories, then why the biggest questions have still remained unresolved. Why do we continue to circle around the same ancient questions; why are we here, what’s our purpose? Where did we come from? What happens after death? Is there more to the world than what we can see and measure? What is soul? In what way are the body and soul united, but also able to part?

Perhaps, only perhaps, the answers are not meant to be discovered by the intellect alone because the observations of scientists and imaginations of artists are but limited tools. Perhaps the fundamental knowledge isn’t discovered or evolved rather revealed.

For the artist, there is a timeless living book, overflowing with wisdom, layered with meaning and radiant with guidance; the Holy Quran. She finds it especially compelling for its conceptually cohesive, spiritually nourishing, and mentally invigorating nature. The

knowledge offered is not only housed in the richest linguistic vessel; the Arabic, but the information itself is part of a rich source; from God.

"Say, O Muhammad: If the sea were ink for writing the words, wisdom, and signs of Allah, the sea would be exhausted before His words were finished—even if We brought another sea to replenish it, and another after that, and more still."